Kevin Cooper’s career journey has been defined by people strategically placed along the way.

Kevin Cooper’s vision of his future, like many young Black men, included becoming a professional basketball player in the NBA, maybe even playing overseas. It didn’t take long before Cooper realized the odds were stacked against him as a professional athlete.

“I played collegiately at Tennessee State University as a part of the 1974-75 NCAA Division II Final Four team and knew I was on my way,” he says.

“But after college, life just didn’t turn out as I had planned it to be.” At the time, Cooper mourned the loss of his dream. But as he traces the path that led to his position today as president and CEO of Infrastructure Professional Services and Equipment, LLC, (InfraPros) he understands that he is exactly where he’s supposed to be.

“Never give up because only God knows your ending,” Cooper says of his minority-owned HVAC and mechanical contracting firm that also helps disadvantaged people ease into the business.

CARVING A PATH

It’s not just his success as a businessman that leads Cooper to believe he followed the right path. It’s the people he encountered along those paths—each one teaching, helping, and encouraging him to go as far as he could and then reach even higher.

He did. But it wasn’t as if he didn’t already have a boost, along his very first path. Cooper’s father, W.C. Cooper, was an agricultural extension agent and 4-H specialist for the state of North Carolina from 1941 until 1974, an impressive position for a Black man in those times.

W.C. Cooper was a humble, spiritual, and compassionate leader, staying in the background while supporting his son and other youths. But there was one thing Cooper remembers his father being adamant about. While stressing the importance of the Black businessman in society, W.C. Cooper encouraged his son to pursue a Business Administration degree after high school.

He still remembers his father saying, “Son, as long as someone else is signing your paycheck

you will never be free.” With that, Cooper forged ahead. He became a Class A commercial painter and home restoration specialist and created his own company, Cooper Residential Restorations.

He quickly demonstrated a head for business. When he encountered problems relying on subcontractors to complete his contracts, he did what any good businessman would do. He learned carpentry, tilesetting, wallpaper hanging, wood restoration, and a host of other trades to cut out the middleman.

While that strategy may have worked, Cooper’s business wasn’t thriving—even though he handled some work for the North Carolina Historic Sites Department. “Still in my twenties, I didn’t have the total business acumen to be really successful, but I was eating every day,” he recalls. “There were ebbs and flows in being your own business owner and once I got married there was a need for more consistent earning capacity.”

EACH ONE, TEACH ONE

That all changed in 1988 when Cooper decided to go into facility management and was hired as a maintenance tech at a local high-end apartment community.

Just as impressive as it was for Cooper’s father, as a Black man, to be employed by the state back in the 40s, it was even more of an anomaly to find a woman in a maintenance position in 1988. But there she was. The maintenance supervisor at the apartment community was a woman—trained in maintenance while serving in the U.S. Army—and she needed someone with Cooper’s contracting and painting skills.

Cooper doesn’t believe it was a coincidence that his supervisor was a woman in a male dominated profession.

“My belief is that absolutely nothing in life is by happenstance but that everything is ordered and a continuing journey,” Cooper says, reflecting on the seemingly coincidental occurrences in his life that not only helped to guide his journey but also helped to shape his character.

As a woman, his supervisor knew that even though Cooper was male, he was a Black male. He, too, would encounter difficulties, as was common in their profession.

So, she trained him. And while she coached him in HVAC, minor electrical repair and replacement, he took advantage of the upward mobility training the management company offered.

“I took every course they had to offer,” Cooper says. “My mind was set on learning and honing my craft so I could be a maintenance supervisor, regional or national director.”

THE PATH LEADS TO A LADDER

In 1991, after accepting a director of maintenance position at another luxury community in nearby Winston-Salem, Cooper began to share his wisdom in the same way the wisdom of others helped him.

“I gave my staff all the information and skills I had to make them better technicians and to one day be in position to take my chair,” he says.

Having prepared his staff to take over when he left, Cooper knew when it was time to move on. He left knowing he had made a difference.

“I took great pride in making every facility better and more efficient than when I arrived and not just in a static position, which causes decay and premature mechanical failure,” Cooper explains.

His last position before moving his family back to Greensboro—as assistant maintenance director of a two-million square-foot mall—allowed him to gain another layer of knowledge.

While there, he completed a year-long certification process to run the facility maintenance department for any shopping center in the country.

Cooper earned the certification while simultaneously running daily maintenance operations and store upfits as well as supervising seven maintenance technicians, a housekeeping department of 13 and overseeing the physical plant team.

“SOMETHING’S NOT RIGHT”

Eventually, he decided to try something a little different. Ok, a lot different. He became an ISA-certified arborist.

As an arborist, Cooper managed a tree company district spanning from Winston-Salem to Raleigh.

Even there, he excelled at his work. In 2002, J. Bennett Brown’s arbor care firm serviced most of the state of North Carolina and he needed someone to supervise the southeast part of the state.

“What stood out to me was his patience, he took notes as I explained what the position required,” Brown recalls. “He was honest about his experience and assured me that he was willing to learn. And learn he did; within one year he became a certified arborist. And (he) expanded our company service area.”

But it wasn’t just Cooper’s work that impressed Brown. He had come across many workers willing to do anything to succeed. Cooper, he says, wasn’t like that.

“There were lines Kevin was not willing to cross to accomplish the desired results,” says Brown, who now considers Cooper a friend.

While Cooper excelled in the arbor industry, something didn’t feel quite right. He felt as though something was missing.

“I have facility management in my blood,” Cooper says of his discovery that he wanted to go back to what he loved. So, he took a position managing facilities for the largest nonprofit agency providing family services throughout the Triad.

DESTINY REVEALED

Cooper didn’t know it at the time, but that decision was pivotal in helping determine the direction of his ultimate path.

He was hired to bring the nonprofit’s assets out of a deep deferred maintenance situation. Cooper assessed the state of the facilities.

He would need help.

“I called on an old vendor friend to help with a plumbing problem as well as antiquated building

control systems and, as it turned out fortunately, he couldn’t help with the controls,” Cooper says.

Yes, Cooper says “fortunately.” That’s because in seeking help, he was introduced to Jeff Farlow, his current business partner at InfraPros and a “building control genius.”

It may have been their shared passion for facility management that kept the two in touch, because they ultimately formed a strong friendship.

“Over the next three years, we became close friends and talked about everything from food to our children’s lives and politics,” Cooper says.

They even talked about the wave of racial unrest triggered by the murder of George Floyd during the summer of 2020. Farlow, who is white, was unsettled over the protests when he called up his friend and told him he was disappointed in the lack of actionable progress.

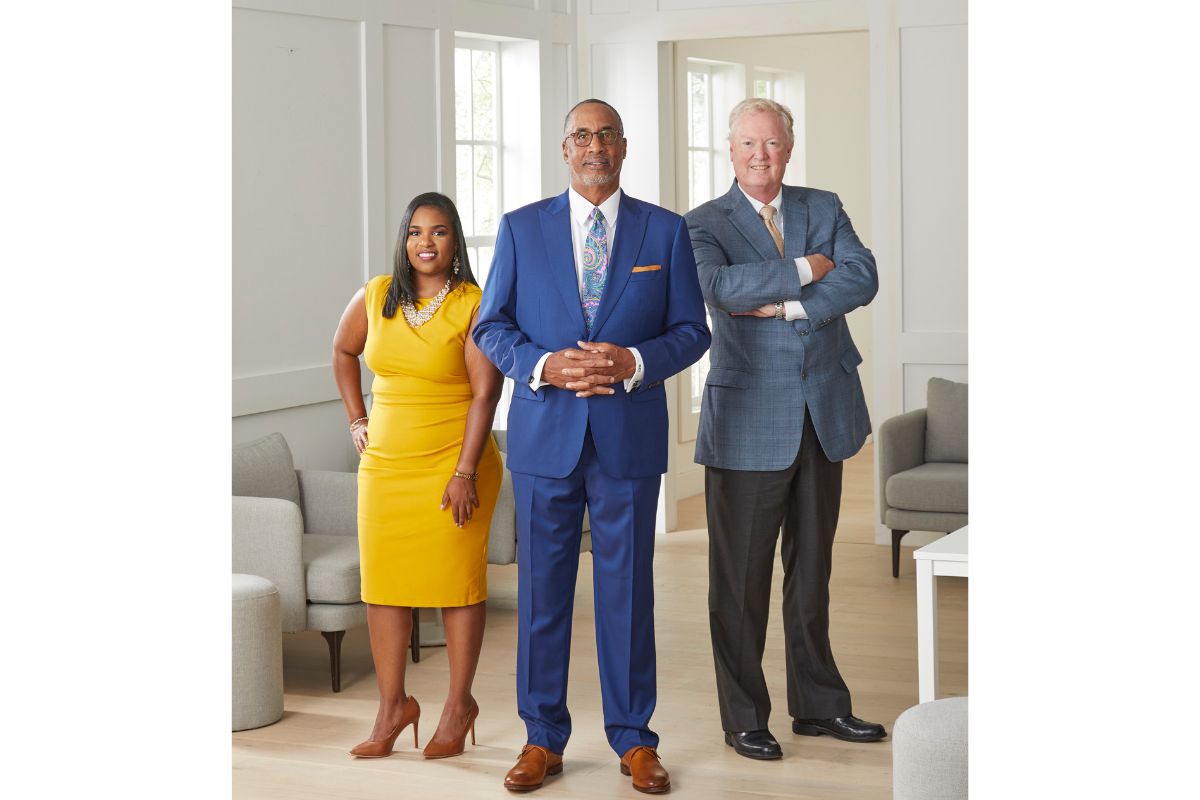

Farlow, now retired, decided that he would take action. He surprised Cooper by proposing that he sell him 55 percent of his company, InfraPros, which specializes in mission critical operations, mechanical and electrical services for facilities such as data centers, healthcare centers, and pharmaceutical sites.

Farlow came out of retirement and the two men decided together that they “would partner and create a mission to bring new faces to an industry that was, and is, generally owned by white people and passed down from generation to generation,” Cooper says.

Once again, Cooper looked back at his path, from the learning opportunities to guidance from others—people strategically placed throughout his journey. He knew what he had to do.

“We could hire underutilized minorities, train them, and make the playing fields level, allowing the cream to rise to the top. And then help those to become mechanical, electrical contractors.”

The assistance wouldn’t end there. They would help the contractors begin their journey by making vendor, banking, accounting, and business networks available to them.

Starting a contracting business from scratch is not an easy process. The introduction to the networks would help to ensure a high success rate.

It was their hope that the contractors realize that two men from vastly different backgrounds can work together to create a business model that will live on and inspire others to do the same.

It worked. Their first hire was A’lexus Monsanto-Harrison, who came in as the accounts and office manager. Now, as InfraPros’ chief operating officer, Monsanto-Harrison has managed the entire operation for the past two years.

Prior to joining InfraPros, Monsanto-Harrison was growing weary at her job in victim services. Then she heard about InfraPros’ mission and the need for more minorities in this industry.

“I had no knowledge of facilities management, mechanical contracting, or HVAC but I knew if I put my mind to it, I would succeed at anything,” she says.

Her success is proudly shared by Farlow and Cooper, who are now part of Monsanto-Harrison’s extended family.

“They both are two positive role models in my life; they have so much wisdom and knowledge in this industry and business. I know they have my best interests at heart, and they see my potential and not just [as] an employee,” she says.

Farlow and Cooper believe their mission is simple: bring historically underutilized minority men and women into the mechanical contracting industry and train them in off-site preconstructed mechanical systems, which will prepare them for the new age of construction for years to come.

“In our own little piece of the world, we can help break the generational wealth curse that has crippled the minority communities,” Cooper says.